Teton Bighorn Sheep Working Group Update – Forethought Helps Bighorns Conserve Valuable Energy by Steve Kilpatrick (Dubois, WY)

Category: Blog

Forethought Helps Bighorns Conserve Valuable Energy

If you think your energy bill will be high this winter, consider the bighorn sheep. You and I pay our fuel bills with our wallets. Bighorns may pay with their lives.

Just before Christmas, the Teton Range were slammed with a historic cold snap. According to the Bridger Teton Avalanche Center, mountain temperatures reached 50 below zero and wind gusts of 100 miles per hour.

You can feel it in your lungs and your exposed skin tingles instantly. Exposed skin is at risk of frostbite within minutes. Yes, bighorns protect their skin with an amazing hair coat, but survival above timberline for an entire season is no doubt challenging.

Yet, somehow bighorn sheep survive weather that would chill a polar bear, even lambs that are only months old and smaller than many of our pet dogs.

In many ways, bighorn sheep are rugged. In other ways, they are fragile. Winter gradually weakens them. Like other wild ungulates, they often lose 20% or more of their body weight, becoming more susceptible to parasite and pathogen invasion. Winter mortality is often prolonged with many not dying until spring.

The Teton Range offers world-class backcountry skiing. It also offers world-class wildlife habitat. Bighorn sheep are the original mountaineers of the Teton Range, but our development, highways and recreational activities have greatly reduced much of their winter range – where past bighorn generations moved seasonally to escape the worst of the weather.

We can continue to have both great skiing and bighorn sheep. All we have to do is think ahead so we don’t continue to whittle away at the winter range bighorn sheep need in the Tetons. This is really nothing new – in the early 1990’s we all worked together to protect winter range for elk, moose, bighorns, and deer on the Bridger-Teton National Forest in our corner of Wyoming.

Backcountry skiing represents who we are, our values. And, so does conserving the original mountaineers of the Tetons – bighorns. Today, the Tetons support only about 200 bighorn sheep. When populations dip that low, biologists worry about animals’ long-term survival. A harsh winter, a disease outbreak or even a big avalanche can make all the difference. Compare those 200 or so bighorns to the 10,000 and more elk that winter on the National Elk Refuge. Bighorns numbers are at about 5% of their historic levels across Wyoming and the West.

So how can we be good stewards of the land and have a great day skiing at the same time? It’s not that hard. The key is planning ahead.

Bighorn sheep are sensitive to disturbance. That is, when they sense a predator (in this case, people) is too close, they often abandon the habitat they are using to find safety. This causes them to burn precious energy, utilize suboptimum habitats and puts them at greater risk to disease/nutrition afflictions, avalanches and other dangers. The best thing we can do for bighorns in the winter is leave them alone.

The Teton Range Bighorn Working Group has used the best science we have – reviewed by outside experts along with local wildlife managers and recreationists alike – and they have mapped bighorn sheep winter range for the public to see. You can download the maps to your smart phone at www.tetonsheep.org.

We already plan our ski days where we think the snow will be best and where avalanche risk is manageable. It’s a relatively simple manner to factor in bighorn sheep winter conservation zones as well.

After planning your own trip, please share the word. Let’s let other skiers, snowboarders and winter recreationists know about these winter conservation zones.

The Teton Bighorn Working Group is also interested in your observations in the backcountry, so please share your insights by leaving a message at 307-739-3558.

We don’t know what 2023 will bring. But this winter has already started with above-average snow fall and below average temperatures. Bighorn sheep will be paying for that harsh winter until spring green up, when they can begin to rebuild their fat reserves. So please keep avoiding those habitat zones well through April.

I’m not usually one for New Year’s resolutions, but here’s one that’s easy to keep. Let’s all be good stewards of the Teton Range, including giving plenty of space to bighorn sheep.

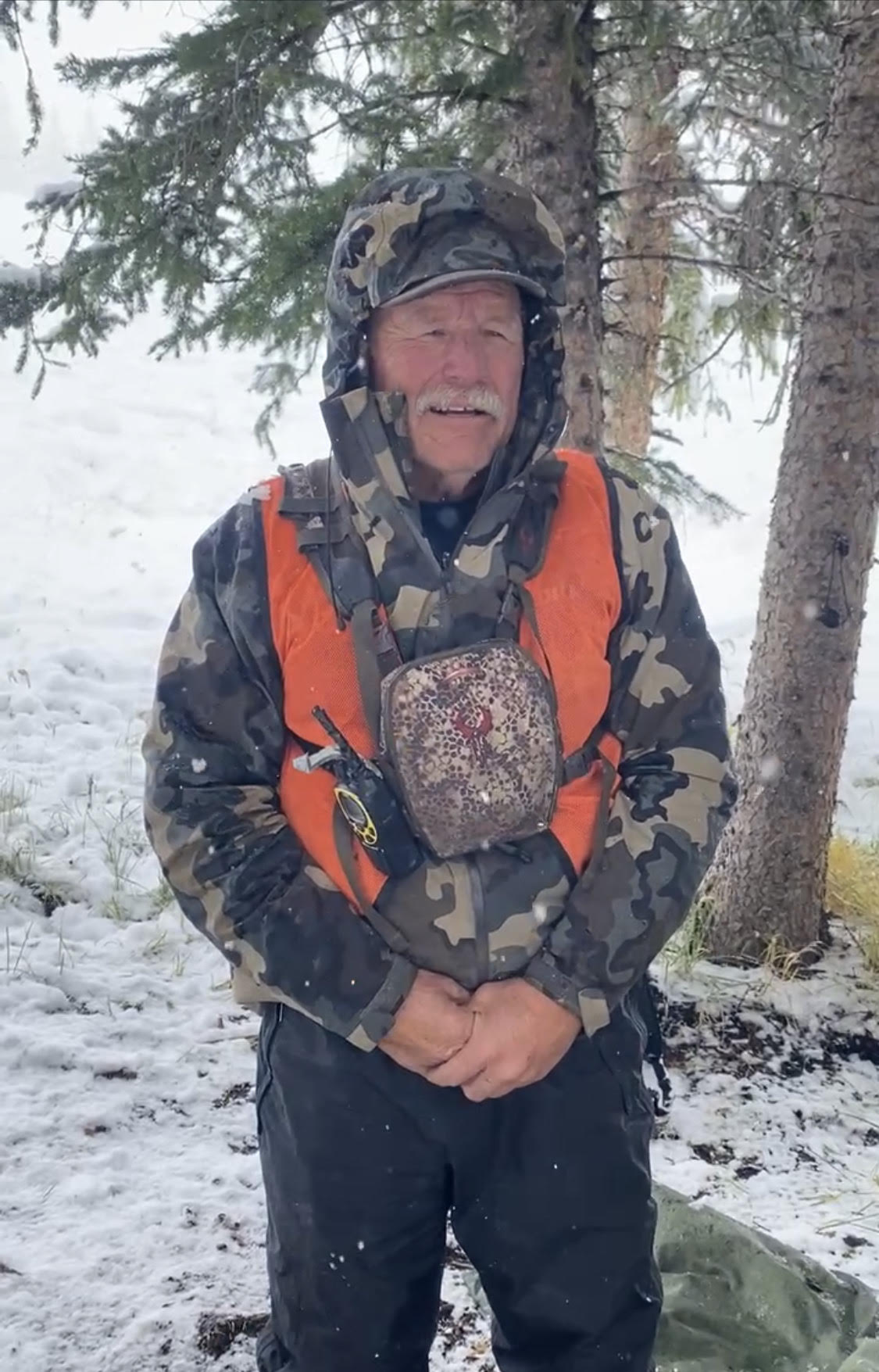

Steve Kilpatrick

Teton Bighorn Sheep Working Group Member

Board of Directors, National Bighorn Sheep Center

How did you get involved with the National Bighorn Sheep Center (NBSC)? When Bill and I moved to Dubois in 2015, Carolyn Gillette told us about the Center and its needs for volunteers. I was retired from teaching at the time and needed to fill my days with meaningful activities. I started volunteering at the Sheep Center shortly after we moved here. About a year after that, Bruce Thompson asked me to join the board in 2016.

What do you like most about being on the NBSC Board? Being a part of the board was a little out of my comfort zone. At first I was intimidated by the knowledge of all the other members, but over time, as I learned more about the Center’s mission, I felt like I was a small piece in the conservation of the sheep. I had a voice to share in the education about sheep and their need for conservation.

What has been one of the most impactful experiences you have had in “wild spaces” and with wildlife? Why? One Thanksgiving, my family took a ride out to Torrey Valley to see the sheep. It was during the rut, of which I had no idea what was involved. We came upon the herd, and the males were doing the usual sniffing, rubbing, and stare downs. We stayed for about 30 minutes watching the performance, when two rams got into position to hit. The sound was so loud and echoed for a second or two. That moment was what hooked me into really wanting to do my part to keep this herd going.

To you, why is conservation education important? And how do you see us ‘moving the needle’ around “wild sheep, wildlife, and wild spaces” conservation? As a former teacher, I’ll always feel that conservation education is important. Without it, people, like myself before I moved here, have no idea what is happening to our animals and their habitats. A lot of adults and children can become interested in conservation by touring the center, and direct education is very impactful. Borrowing education trunks, visits to schools from staff, and classes through the center are all great ways to spread the word about conservation. What I think is a strong way to get future conservationists hooked is by immersing them in the habitat where the wildlife live. The summer camp is one of the best ways to get kids passionate about sheep and the environment. They are essentially experiencing the terrain, food, and some of the challenges that the bighorn sheep encounter, making it real and tangible.

What advice do you have for the next generation looking to get involved in conservation? This is what guides me to take part in conservation: Think about the first time you encountered wildlife or a habitat that took your breath away. Remember how excited you were to share that experience with someone else. Without conservation, it won’t be there to share with future generations. It won’t be there for others to get to feel the way you felt. Small things can make a big difference, do what you can to take part…just take part!

Is there anything else you would like to share with us about yourself and your journey towards conservation? I would just like to thank those who lead me toward a passion for conservation, Carolyn Gillette, Bruce Thompson, Sara Domek, Karen Sullivan, Sara Bridge, and most of all, my husband Bill. Without their dedication for the Sheep Center and the sheep, I would not have had the experiences and education that I’ve had, and be able to pass it on to the next generation!

IN MEMORY OF DAVID CHARLES LOCKMAN

1947-2022

Dave Lockman earned a Bachelor of Science in Wildlife Biology and Range Management from Colorado State University in 1969 and a Master of Science degree in Avian Biology from CSU in 1971. He worked as a field biologist for the Wyoming Game and Fish Department (WGFD) for nineteen years and retired from the Department as Education Supervisor after thirty-two years of service.

During his tenure as a wildlife biologist, Dave made significant contributions to Wyoming’s wildlife, whether it was testing new data collection techniques for big game or improved management techniques for waterfowl. Dave had a great interest in wetlands and waterfowl. He was the WGFD Western Wyoming Waterfowl Manager for many years, restoring and expanding trumpeter swan populations in Wyoming. He conducted inventories and population surveys, designed management plans, initiated the wetland mapping and classification system used by USFWS for Wyoming wetlands, organized the first Rocky Mountain Trumpeter Swan Population Management subcommittee for the U.S. and Canada, organized the Whooping Crane Management and Recovery Effort for Wyoming, and authored or co-authored numerous technical articles during his career.

While Education Supervisor, Dave prepared and supervised the implementation and management of over 20 cooperative agreements with Wyoming communities and developed over 50 interpretive education projects, supervised the development of the Outdoor Recreation Education Opportunities program for Wyoming schools, coordinated the establishment of the National Bighorn Sheep Center in Dubois, Wyoming, and created wildlife viewing sites across the state as part of the “Wyoming’s Wildlife-Worth the Watching” program. He planned and developed the first Wyoming Hunting and Fishing Heritage Exposition hosted by the Department. This became an annual event in Wyoming for over 13,000 families and youth annually. He co-authored the “Outdoor Expo Planning Guide”, a collaborative effort between the Weatherby Foundation, Texas Parks and Wildlife Department, and WGFD. This guide was a practical handbook for states desiring to produce an Outdoor Expo. In 2003 he became the project leader for the Weatherby Foundation’s North American Outdoor Expo Campaign. This included providing planning assistance to states and managing a national grant program for funding support to states. As a result, twenty-two states implemented Outdoor Expo education events, reaching 350,000 participants annually.

Since his retirement from the Department, Dave worked as a private consultant on numerous intensive wildlife and habitat surveys, habitat evaluations, and designed and implemented wildlife habitat improvement projects for private landowners and the oil and gas industry. Dave will long be remembered for his tireless efforts with management plans for Pathfinder Ranches, wetland development and designs, habitat inventories and mule deer mitigation work on the Jonah Oil Field, and the Bridger-Teton Forest internship for ecology and forest management.

Dave Lockman was inducted into the Wyoming Outdoor Hall of Fame in 2014. One may make contributions to the National Bighorn Sheep Center’s Conservation Education Fund in memory of David Lockman.

Bighorns and Skiing Can Live Together

Category: Blog

Not everything is as it seems in nature.

Take bighorn sheep. Few animals appear as rugged and tough as a bighorn ram, with its muscular body and burly horns.

Yet bighorns are remarkably fragile. They’re susceptible to human stress, winterkill and disease. That’s why since the 1800s these magnificent animals have lost 95% of their range and exist at only 5% of their historic numbers. Given this history, it’s easy to imagine that the Tetons could become yet another mountain range that “used to have” wild bighorns.

Bighorn sheep biologists have been working to conserve the native and rare bighorn herd of the Teton Range to prevent local extinction. This winter we have reached two landmarks in these stewardship efforts.

These bighorns have survived in the Tetons for thousands of years. However, like elsewhere, numerous factors have lowered and restricted their numbers and distribution. Many of these factors are linked to humans — habitat alteration, livestock disease, disturbance, broken migration routes, past overhunting.

Biologists from the National Park Service, U.S. Forest Service and Wyoming Game and Fish Department put their brain power together in the early 1990s to form the Teton Bighorn Sheep Working Group. We solicited the advice of dozens of leading bighorn sheep biologists from both Wyoming and the rest of North America.

The science was solid and agreed upon — a rare unanimous professional consensus. The bighorn sheep professionals agreed on two urgent concerns: One, address the problem of nonnative mountain goats, which can spread disease and compete for food in the Tetons.

Two, address human activities that put stress on the animals, particularly winter recreation that occurs when bighorns are on starvation rations.

Just this month Grand Teton National Park completed its fourth mountain goat cull. It is an unpleasant, expensive and dangerous task with no shortage of controversy. It would have been easy for agency decision-makers to sweep it under the rug, but they did not.

Next is the issue of backcountry recreation. The Teton Bighorn Sheep Working Group agreed that an all-inclusive public collaborative process would be essential in addressing winter backcountry recreation. Many of us are backcountry skiers and keenly aware of the need for skier support. We worked our tails off soliciting substantial funds to hold five large public meetings and dozens of smaller listening sessions. We have spent more than three years welcoming skiers as partners in this process.

We heard a clear message from skiers: While they valued their freedom to roam the Tetons, they also respect bighorn sheep and want to be good stewards of the land.

While some observers recommended that “every remaining acre” of bighorn winter range be protected, we did not want to paint with such a broad brush.

Based on our conversations with the local ski community, we focused on the most critical half of winter range. Skiers went on to identify opportunities for traverses and other flexibility.

This winter the Forest Service and Park Service have asked skiers to voluntarily avoid critical bighorn sheep winter range. The Bighorn Sheep Working Group provided maps of these areas to skiers, both to be printed or to be incorporated in handheld navigation devices using GPS. The maps are available at TetonSheep.org.

So far skiers have largely supported the Teton Bighorn Sheep Working Group’s and agencies’ recommendations.

The group works hard to listen to both the scientists and the wisdom of local skiers. The science behind the research continues to be cutting edge and reviewed and supported by many field professionals and university researchers.

Do we need more data? Certainly. Always. We are interested in what skiers observe and urge them to report their experiences and insights at the hotline available at TetonSheep.org.

We biologists also continue to seek out the best, most accurate way to survey sheep numbers in the first place.

In the end the story is simple. Bighorn sheep in the Tetons are eking out a living, some in the harshest winter habitats. The best way to conserve these sheep long into the future is by grassroots stewardship.

We sincerely appreciate your engagement in the collaborative efforts and associated conservation of the Teton bighorns. Let’s use our passions and what we know about the bighorns to do the right thing, before it’s too late!

Can we enjoy both bighorn sheep and some of the world’s finest backcountry skiing in the Tetons? Yes, if we work together.

Steve Kilpatrick is a biologist and member of the Teton Bighorn Sheep Working Group. He lives in Dubois.

How did you get involved with the National Bighorn Sheep Center (NBSC)? We saw the Center from the outside on one of our first trips to Dubois. I remember thinking, “How can a little tiny town like Dubois, with 900 people, have a national center dedicated to conservation, like the NBSC? Then Cindie [my wife] took our friends Alan and Levan, who were some of our first visitors in Dubois, over to the Center for a tour. I didn’t get to go with them because I was unpacking the U-Pak trailer. Then we met Kathy and Lary Treanor at church and Kathy talked us up about the NBSC. The rest is history.

What do you like most about being on the NBSC Board? I think what I like best about being on the Board is the diversity of the group. We have people from allbackgrounds. And all these diverse people are passionate about the wild places and wildlife that surrounds us.

What has been one of the most impactful experiences you have had in “wild spaces” and with wildlife? Why? Many years ago, Cindie and I were hiking up Cascade Canyon in the Tetons. I remember hearing these little “beep beep beeps” up in the rock fall. It turned out that there were Pika’s up there running around making all the racket. I remember wondering about how something so little and cute could survive in such a huge, rocky, and dangerous place like that canyon. I later found out that because of climate change, the areas where Pika’s can survive is changing. They are having to live higher up in the mountains then they used to. I felt then, and I still feel today, very responsible for doing that to the Pika’s. I want to make their lives better, not worse. They are my buddies.

To you, why is conservation education important? And how do you see us ‘moving the needle’ around “wild sheep, wildlife, and wild spaces” conservation?

I think the most important thing to remember is that we can make this better, we can fix this. With all this bad stuff happening because of climate change, it’s easy to lose faith. But we humans are capable of so much. We can and we will fix all the hurt we have inflicted on our planet. We just never know how it’s going to turn out, but we must know that it will turn out perfectly.

What advice do you have for the next generation looking to get involved in conservation? Don’t give up on conservation. It will be hard work and you might not see how it will get better. But it will getbetter, and you will have a hand in making things better.

Is there anything else you would like to share with us about yourself and your journey towards conservation? I love looking at pictures of our planet taken from outer space. All my life I’ve always drawn pictures and have always wanted to be an astronaut. I might not make it to space, but I’ve seen pictures. I know that things need to be fixed and they will be, we will do it. Just like we put people on the moon, we will solve this climate crisis and we will help the Bighorn Sheep rebound.November 2021

A letter from our Executive Director

Category: Blog

Friend,

Little did the gentleman know he helped save my life when his Chevy pulled up in my driveway upon one text message: “Can you drive me to the hospital?” This implied a two-hour drive one-way, in the dark, across a steep and winding mountain pass; he did not hesitate. And that’s Wyoming.

The evening of Wednesday September 8th I fell gravely ill. The 26-day hospital stay, 10 days on a ventilator, and 30 days of lung collapse that followed only strengthened my love for Wyoming, our small community, and the values that define us. The remoteness, wildness, of Dubois attracted me here. 70 miles from any large grocery store, fast food chain, let alone hospital, where better to truly connect with nature and all the lessons it teaches?

Admitted into the ER with fever, body aches, and cough, the staff tested for COVID-19. Negative-consistent with the rapid test I had taken that morning. Each doctor and nurse that came into my room listened to my lungs. My pain and wheezing: increasing. I understood the seriousness of my condition when one nurse said, “Her lung hasn’t collapsed yet.” Staff struggled to both remain calm and attempt to calm me, aware that my x-ray showed a complete “white-out” of my right lung. All infection; no lung. My white blood cell count read 1,000x the normal. They explained I had pneumonia. As nurses monitored my oxygen levels, it was clear I could not breathe on my own, and in just hours, the condition worsened despite nebulizers and a BiPAP oxygen mask.

On September 15th I came back to consciousness, on a ventilator, to find my dear sister and father by my side. This was their first time in Wyoming. They explained I had been diagnosed with the Pneumonic Plague. Yes, the Black Death that decimated nearly one-third of Europe’s population in the 14th century.

As my condition improved with the proper antibiotics, my sister began to describe the prayers sent, the food they received, the fund created to help with medical bills, and the expertise and compassion of St. John’s Hospital staff. I cried. She explained, “This [response] would never happen in New Jersey…”

Despite the circumstances, she saw the best of our community and our values. WY are we different? Our personal experiences in Wilderness and with its wildlife, much more abundant here, connect us to our deepest humanity. Experiences in the outdoors cultivate a sense of dignity, compassion, and responsibility to all things: humans, animals, and lands; a togetherness you don’t find in cities.

As my treatment continued at the University of Washington Medical Center, doctors explained the graveness of my illness. I know how lucky I am to be alive. Though I explained to any willing listener that I had already seen Heaven, heck, I live there!

Friend, I am back and glad to write you this letter. This experience has deepened my confidence in the power of personal connections with wild spaces and wildlife. How honored I am to work towards this with you throughthe NationalBighorn SheepCenter’s educational programs and future classroom expansion.

I’d like to thank our phenomenal staff, Dubois community, and supporters across the nation who have helped in this trying journey. In my absence, the team launched our “Big 4” Virtual Raffle. Visit our website to enter and support our mission to provide education and outreach for the national conservation of wild sheep, wildlife, and wild lands.

Talk to you soon,

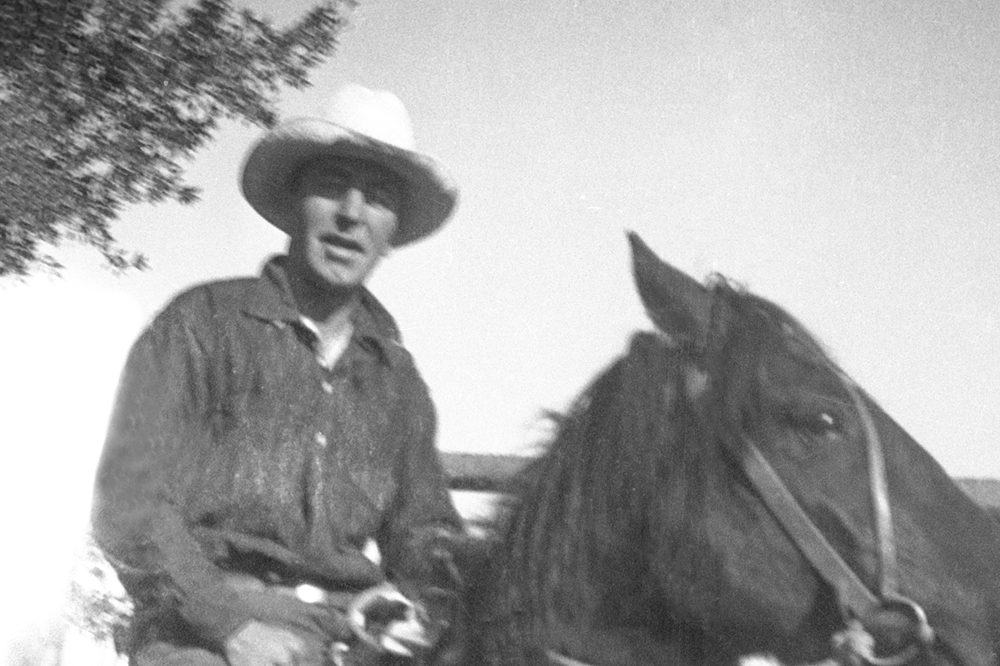

Dubois locals, Meredith and Tory Taylor, the first official joiners of our Legacy Society, and leaders in conservation, talk “lives lived large, elk-feed, and horses”

Meredith and Tory Taylor have been outfitters, guides and conservation leaders in the wild heart of Wyoming’s Greater Yellowstone for almost 50 years. Over those decades, they have explored places few others have ever seen, shown generations of Americans the wonders of hunting and fishing and wilderness, horses, wolves, storms and stars, wildflower meadows and summer snowbanks, tumbling whitewater creeks and towering black-rock peaks. Theirs is a marriage and an adventure partnership, based in their modest home and native plant gardens and horse pastures on the Wind River, carried as far afield as Outer Mongolia. Join us for a wide-ranging discussion of lives lived large, elk-fed, and mostly on horseback.

Memoirs of a Free Spirit, A Story of Dubois Homesteader Now Sold at the National Bighorn Sheep Center

Recently, while visiting and working on the many different projects going on at Jack Anderson’s Home on the Wind, we had a few visitors. It is not unusual to just drop by and say hello to your neighbor in Dubois, Wyoming after all. But much to our surprise, this was a lady in her 90s who was passing by and asked her son and his girlfriend to turn down the driveway.

Belle Epperson was so excited to see and talk to us. She had a lot of stories to tell about her own time as a young girl living with her mother on Jack’s ranch in the 1940s, and later as a caretaker of the Schwinn property and the Blue Holes. Those days on the Wind River were some of the best times in her life, she says. Belle graduated from Dubois High School in 1944 with only 7 people in her class and moved to Riverton in 1946, having married at 18 years old.

Belle’s mother, Blanche Morris and Jack were friends in their teens in and around 1912-1914. Kids who grew up on family farms. Belle’s stories of Blanche and Jack as childhood friends mirrored some of the same early life stories that Jack describes in his book Memoirs of a Free Spirit. While Blanche’s family lived in Bellevue, Iowa, nothing stopped kids in those days from crossing the Mississippi River to Hanover or vice versa to hang out with each other. They would go sledding in the winter and berry picking in the summer, and these rural farm families would get to know each other well.

These early stories were just the start of a life of adventure for Jack Anderson. In his book Memoirs of a Free Spirit, Jack sets out, at just 14 years old, on an open-minded-with-WOW!-factor journey which would eventually land him more permanently in Dubois around 1919. Leading up until then, Jack refused to stay in one place for long, taking on nearly any job to survive! One must laugh at the way Jack describes his experience as a boat hand on a stern wheeler steam tugboat (turned logging pirate ship) on the Mississippi. The jokes he and others played on friends and strangers and train hopping would land any of us in legal trouble today. Even Jack’s experiences in World War I, from training as a motorcycle mechanic, to serving in the 148th Field Artillery in the motorcycle brigade near Verdun, France, leads him back to Lander, Wyoming — via Leonard Young who Jack saved from the trenches overseas. There is so much in between these tales you must read!

In Memoirs of a Free Spirit, Jack tells his story just as he would speak to you, with a bold voice and dry sense of humor and in his own special vernacular. Each chapter unfolds quickly. You can hear his voice telling you, “That’s not all! You’d better keep going.” He makes you want to read more, knowing that another unexpected scenario is just around the corner. This book is a fun and quick read.

Originally self-published by Jack in 1980 and with few copies remaining, his grandchildren decided it was time for a 2nd edition of Memoirs of a Free Spirit. The new edition now includes a comprehensive Addendum of photos and descriptions — parents and siblings; hunting and World War I memorabilia, poems, Jack’s sourdough pancake recipe, personal memoirs of Jack by current family members, and a Reference section of people and businesses with whom Jack had close association in and around in Dubois.

Many years later, Jack and Blanche’s deep bond as kids would bring them together again, this time in Dubois, with Belle, during World War II years when many had left the area to work in defense plants in California or to serve. After the war they parted once more, but remained friends. This period in Jack’s life is not accounted for in his book, nor is his family life with my grandmother Lucile and their children in the 1920s to early 1930s. There are just as many fantastic, adventurous, and heart-breaking stories in these chapters that could easily be a sequel to Memoirs of a Free Spirit.

You will really enjoy Jack’s book. How far we’ve come! Or have we?

Dana Cheatham Scoby

Editor Jack Anderson’s granddaughter

[email protected]